While using Noteflight, perhaps you have wondered: “why can’t I make the key signature different in my clarinet part?” Or perhaps you clicked “Add Part” or “Change Instrument” in the Staff menu, and you wondered about the popup window that appears, with its three options: Instrument key, Instrument octave, and Score octave.

This article explores the reasons behind these options, and shows how to use them in your scores.

Instrument transposition is probably one of the most confusing topics in music, so let’s begin with a little background. What IS a “transposing instrument”, and why is such a confusing thing allowed to continue?

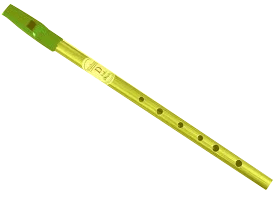

For the most part, the transposing instruments are the woodwinds and brass, and it has to do with the physics of how they are constructed (for most stringed instruments like the violin or harp, we do not need to worry about this issue). A woodwind instrument is a simple tube, with holes for changing notes, like this penny whistle:

Counting the hole at the open bottom of the instrument, you can see seven holes. These allow you to change notes from the lowest one (all holes closed) up seven notes of the diatonic scale to one note before the next octave (the seventh scale degree, or “ti”). To continue on to the note one octave above the lowest note, you must “overblow” – i.e. increase the intensity of your breath (the clarinet is similar, but it overblows at the octave-plus-fifth).

The more complex woodwind instruments with full chromatic scales, like the flute or the oboe, fundamentally work the same way: like the pennywhistle, they are built around that lowest note and the octave above. The whole instrument is therefore considered to be “in the key” of that pitch. If it’s a chromatic instrument it can play in other keys, but that key is still the “default” or basic key because the fingering is simplest.

Some instruments, like the oboe, are built in C: their “basic scale”, from the lowest note (or close-to-lowest) to the note an octave above (which they reach by overblowing), begins on an actual C. Other instruments start their basic scale on a different pitch: for example a clarinet in B-flat begins on — you guessed it — B-flat. Wind instruments that are longer produce notes that are lower.

Why you need to know

Here’s why this matters for music notation: if the clarinetist plays their basic scale on a B-flat clarinet, they start on a B-flat. But clarinets come in other sizes: the clarinet in A, with the basic scale of A (a slightly bigger instrument, one half step lower) and the clarinet in E-flat (a smaller instrument, one fourth higher). But the fingerings are the same on all clarinets: if you play a B-flat major scale on the B-flat clarinet, it feels exactly the same as playing an A major scale on the A clarinet or an E-flat major scale on the E-flat clarinet. It would be confusing if they had to read different pitches and different key signatures for the same fingering! So at some point in history, someone decided that the first note of the basic scale on any clarinet should be written as C, even if that note sounds like B-flat, or A, or E-flat.

So in “transposed” score, or a transposed individual part for a clarinet in B-flat, a written C will actually sound like a B-flat: one whole step lower than written. The same applies to any other note: a written G will sound like an F; a written C-sharp will sound like a B-natural. Now think about the A clarinet: the same basic idea applies, but with a different “interval of transposition”. Written C will sound like the pitch A, one minor third lower. Written A will sound like F-sharp, and so on.

The opposite of a “transposed score” is a score “in concert pitch” — which means that all the pitches are written as they sound. This makes it easier to see immediately what the pitches really sound like: a C is a C, an F-sharp is an F-sharp. But if a B-flat clarinetist plays from that un-transposed score, it will sound all wrong. They will see the F-sharp, and will play the fingering for their F-sharp, which is really a “concert” or “sounding” E natural.

Viewing Scores in Concert or Transposed Pitch

The difference between a transposed score and a concert pitch score is ONLY in how it looks. If all the transposing instruments read from properly transposed parts, everything will sound right. When you are using Noteflight, you can toggle between these two viewing options using the “Concert pitch” button at the bottom of the screen. If you uncheck it, you will see all the transposing instruments as they see their parts. But the pitches you read will not be the pitches you hear.

Try it, using this score. All the instruments in this score except the flute, piccolo and guitar are transposing (though see below about the piccolo and guitar), so their written pitches will change, but not the sounding ones.

It’s important to remember that this is purely a notation issue: if you press play, the score will sound the same whether you have “Concert pitch” checked off or not.

Key Signatures for Transposing Instruments

To avoid adding lots of accidentals, Noteflight automatically changes the key signatures to match — this is standard practice for transposing scores. For example, the tune in this score is in the key of F at concert pitch (look at the flute: because it is a “concert pitch instrument”, it won’t change when you uncheck “Concert pitch”). But the French Horn in F, which sounds a perfect fifth lower, must be transposed up a perfect fifth when written in concert pitch — to the key signature one fifth higher than F, or C major (remember your circle of fifths!). So when the horn player plays their “C”, it will sound like an F below to the rest of us.

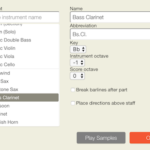

Using the Dialog Box

So let’s get back to that pesky — but necessary — “add part/change instrument” dialog box. For many common instruments, like the piano, violin or flute, the default options for Instrument key, Instrument octave, and Score octave will be, respectively, “C”, “0” and “0”. This is because these instruments are non-transposing: they sound “at concert pitch”. But if you choose the clarinet, the “key” option will default to “B-flat”. If you choose the bass clarinet the Instrument Octave will be “-1”, and if you choose piccolo, the Score Octave will be “-1”. What do these settings mean?

We have already discussed the “Instrument key” option: it’s the note which that instrument reads as “C”. 99% percent of the time, you should not change this, because Noteflight already knows the correct transpositions for the standard instruments. But occasionally this will be useful. If you want to write for the clarinet in A, you must change the default “B-flat” to “A”. However you must be careful to stick with instruments that actually exist: there is no such thing as an “F-sharp clarinet”, so you should never use that option!

Although Noteflight automatically transposes instruments that need it, the default score view is “Concert pitch”. So the transposition information is correctly stored in the program, but all the instruments will appear at concert pitch to make it easier for you, the composer/arranger/viewer, to read without having to do the mental gymnastics of instrument transposition: “wait, I’m reading a B-flat in the clarinet, so is that a C, or an A-flat?” — believe me, even experienced composers get confused by these transpositions!

However, because players must always read from transposed parts, Noteflight Premium automatically prints individual parts at their correct transposition. And it’s often useful for the composer/arranger to look at a transposed score, so they can see exactly what the player sees. It helps a composer to write idiomatically for each instrument: each instrument has certain fingerings or note movements that are harder than others, and if the composer thinks in terms of that instrument instead of concert pitch, it makes them more sensitive to the nuances of the instrument. On a more practical level, viewing the transposed score can help avoid problems like too many ledger lines. Look at the bass clarinet part in this sample score: when you uncheck “Concert pitch”, it jumps all the notes up above the staff. To make it easier to read, the composer could use a different clef, or an octava line, in the part (but not in the score).

Conductors’ scores are usually printed out as “transposed” rather than “concert pitch”. This makes it harder for them to quickly name the sounding pitches, but it pays off because it makes rehearsal much easier. The conductor can say “clarinets, begin on the D-flat in measure 47!” and the clarinet players can look at their part and see the same written D-flat, without anyone having to do any mental transposition.

Instrument Octave

What about the “Instrument octave” option in the add/change instrument dialog? This is just another aspect of transposition, at the octave. The bass clarinet is a great example: like the clarinet in B-flat, its basic scale is B-flat: when the player reads a “C”, it sounds like a B-flat. But with the bass clarinet, it also sounds an octave lower than the B-flat of a regular B-flat clarinet. So the bass clarinet transposes a step-and-octave, or a major ninth, below its written pitch. Because its written pitches are so much higher than its sounding ones, it is usually written in the treble clef (that way the player doesn’t have to worry about reading bass clef). The Noteflight dialog takes care of the two aspects of its transposition, step and octave, in two separate steps: first the “Instrument key” (Bb), and then the “Instrument octave” (-1, i.e. one octave lower). Look again at this sample score to see this in action.

Score Octave

Finally, the third option in the dialog, the “Score octave”. This is for transpositions of an octave up or down, that are implied rather than written. The piccolo is a good example: in both a transposed score and a concert pitch score, a sounding C on the second-to-top line of the treble staff is written an octave lower as a middle C. Thus the “Score octave” in Noteflight is “-1”. As long as everyone remembers that, it causes no problems and it avoids lots of ledger lines.

The acoustic and classical guitars in Noteflight work the same way, but in the opposite direction: the guitar is written an octave higher than it sounds, so the “Score octave” is “1” (meaning “display this 1 octave higher than it sounds”).

One last time, look again at this sample score to see how this works.

Last but not least…

Two other important things to keep in mind. First: after you have finished with the “change/add instrument” dialog, you can always go back and change it again later if you need to, using the “Staff > Change Instrument” function.

And finally: this entire discussion is separate from the options under the Edit > Transpose menu, where you can move notes or whole sections/pieces up or down by steps or octaves. This feature changes only a selected passage, and — the key point — it affects both concert pitch and transposed pitch. Thus it’s completely different from the instrument-based transposition we have been discussing, which is just different ways of *displaying* the same exact sounding notes. The options under Edit > Transpose actually *changes* the way the music will sound, so don’t get these features reversed!